I love eccentricities. I will value you if you are kind, witty, and a good listener, but if you sing off-key with gusto, wear a signature bow tie, or tend to laugh at your own jokes, I will love you even more. After all, when Albert Einstein’s doctor forbade him from buying tobacco for his pipe, the genius circumvented his doctor’s orders by stooping to pick up discarded cigarette butts off the street to stoke his bowl. I like that about Al.

I love eccentricities. I will value you if you are kind, witty, and a good listener, but if you sing off-key with gusto, wear a signature bow tie, or tend to laugh at your own jokes, I will love you even more. After all, when Albert Einstein’s doctor forbade him from buying tobacco for his pipe, the genius circumvented his doctor’s orders by stooping to pick up discarded cigarette butts off the street to stoke his bowl. I like that about Al.

My father was a man of many eccentricities. They caused a great deal of conflict in our family, especially from my mother.

For one thing, my mother valued the neat uncluttered line, and my father was a cluttery saver. Old church bulletins peeked out from his Sunday suit pockets and then stacked themselves along the dresser. Every birthday card he ever received was saved somewhere between the pages of his beloved books. His wallet was an overstuffed piece of leather padding his behind and containing moldering treasures: his daughters’ lost baby teeth folded up in yellowed paper, snatches of Bible verses and poetry he wanted to commit to memory, receipts for goods that had long been paid for, and the business cards of people he had long forgotten but still intended never to forget.

My mother, on the other hand, was the ultimate white-gloved housewife. When we had a family meal, she could swoop down and catch a wayward pea before it ever reached our lap. She could spot a dust bunny at 50 paces. So you can imagine the conflicts that arose over my father’s most passionate eccentricity: his love for cigars. My mother was convinced that she had married a very good man with a very bad habit.

We children felt different. Growing up in the years before the surgeon’s general report tied smoking to horrendous diseases, we looked on the cigar rings that he gave us as tokens of his affection. We treasured his cigar boxes as special places to keep our paper doll clothes, our Brownie badges, and our crayons. We loved the way he blew smoke rings for our amusement. We giggled in amazement as we watched him make a cigar ring disappear behind his ear.

However, my mother was not amused. The way my father coped with this stand-off was with six words, “Honey, I’m going to step outside.” Over the years, we children learned to understand that “stepping outside” meant that a treasured time was now coming for Daddy’s daughters. He was a Southerner and thus a storyteller, and stepping outside meant we got to sit at his feet and listen while he smoked and regaled us with his tales. One of my favorites was the one he told about the happiest day in his life. Into his 80s, he could still remember it.

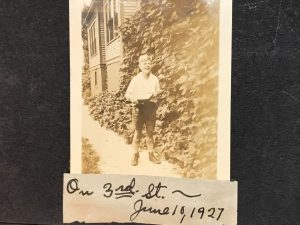

The story was about the day he turned 10 years old. It was during the depression, and the family fortunes had turned downward. His father had lost his job. They had lost their home. The family was living in a boarding house, and my father recalled that often strangers appeared at the back door begging for food. In a year like this one, my father didn’t dare to expect a birthday present. To his everlasting joy, however, he received a very special box on that day, a box of toy soldiers, the birthday present he hadn’t dared to hope for. My favorite picture of him is one he saved over the years from that very day so long ago. It shows him grinning from ear to ear, clutching that box of toy soldiers. Whenever he told that story, my father reminded us that even in the difficult times, there is still joy to be found.

One of the hardest parts of dealing with the death of a loved one is that it seems impossible that they could somehow be gone. Natalie Goldberg writes of this sense of unreal dislocation: “Over a lifetime, we’ve said good-bye in all sorts of ways: good-bye, I’ll see you later; come back soon. But these are ‘casual leavings,’ not ‘eternal departures.’ You think, ‘Well, sure they died, but when are they coming back? When will they walk through the door? Never? How is that possible? I still have so many things I want to tell them.”

That sense of still having so many things to tell them says to me that we are still in relationship with those we have lost. It’s perhaps like the way an amputee feels about a severed limb. It’s still there. You still feel it. It may be gone, but it is still a part of you. And often what you miss most is their off-key singing, their signature bow tie, or the way they made a cigar ring disappear behind their ear.